What might a roguelike look like if it featured a thinker and explorer instead of a traditional warrior? If being clever was more important than being strong? That’s a design challenge we’ve attempted to tackle with Road Not Taken.

You play a ranger in a frigid, enchanted forest trying to save lost children. You start with a few easy-to-learn abilities. You can pick up any adjacent objects, you can carry them around, and you can throw them. Trees, boulders, bears: they all float at your command. But you need to be careful; whenever you carry things, it costs you stamina. If you run out of stamina, you collapse face-first into the snow. No checkpoints, no re-loads; it’s over.

The environment is the threat

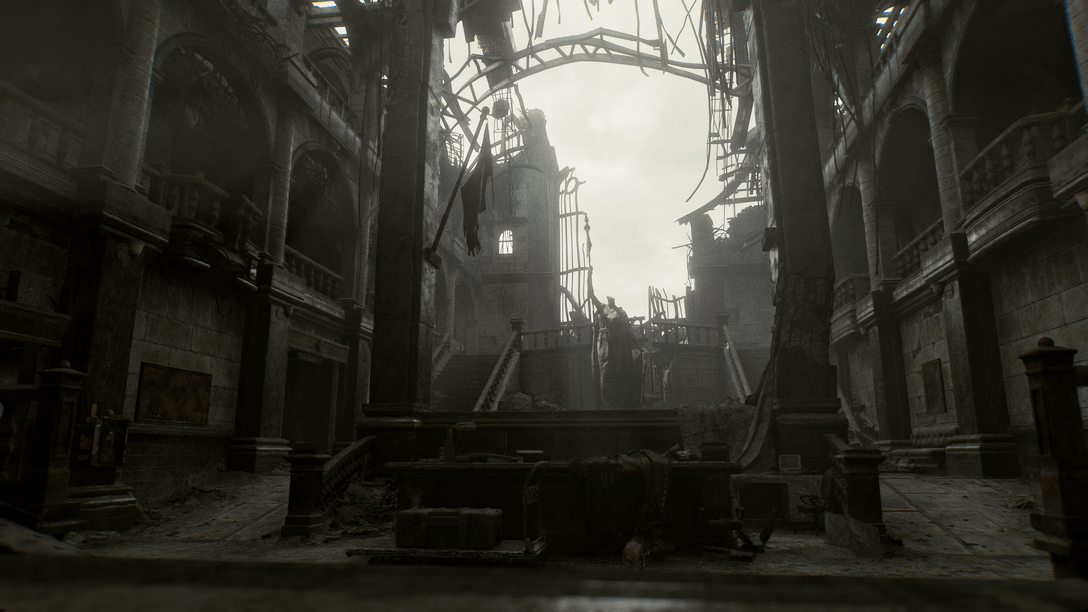

In Road Not Taken, both the challenge and the exciting moments come from the setting itself. You’ll be intrigued by strange objects that you haven’t encountered before and whose characteristics are never fully explained. There are wild creatures running about, spiky plants that hurt you if you pick them up, wolves and blizzards that sap your strength.

There isn’t a clear way into or out of the heart of the forest, and to make matters worse, the exit to every area is blocked. It’s a chaotic and dangerous mess, and you’ll feel the intensity ratchet upwards as your stamina decreases step-by-carefully-planned step.

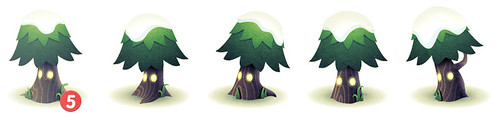

You unlock the exits to a section of the forest by organizing the chaos with your powers. Say, for example, that you’ve got an exit blocked by rocks, and you notice that it requires five trees to open. You look over the map and spot a bunch of trees blocked behind various rocks and creatures. Being incredibly smart, you start moving things around and eventually collect the trees together into a single, connected set. Voila! The exit rumbles open.

Unique objects with unique behaviours

Organising the chaos is trickier than it looks. You could simply lug trees into position, but you’d end up draining your energy and eventually succumb to the winter storm. And on top of that, you have to deal with all the unique creatures and objects in your way, each of which have their own unexpected ways of moving, combining and/or draining your stamina.

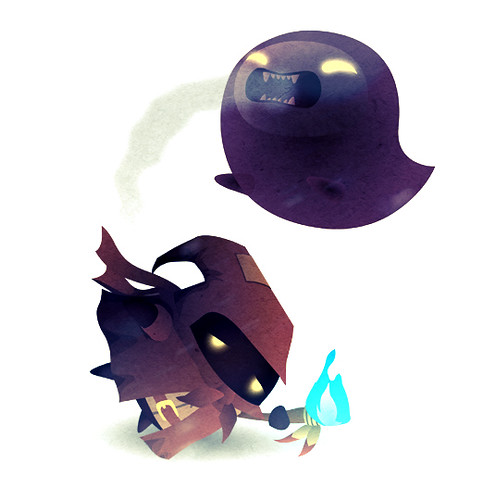

In Road Not Taken, you improve mainly by learning how things work and learning to play more strategically. For example, moles burrow under things. That doesn’t seem very useful until you figure out that this lets you shift otherwise-immoveable stones around. Forest spirits hurt you if you walk into them, then they vanish. But spirits can also help you… if you learn to unlock their secrets.

And speaking of secrets: they are everywhere. Sometimes I think of Road Not Taken as this giant treasure box of secrets. Some objects magically combine into new objects that restore your stamina or serve as powerful tools for you. Other objects seem totally useless until you discover the context that makes them helpful. (What’s up with that goat, and why is he pooping all over the place??)

The Behaviour System

Behind the scenes, the objects in Road Not Taken use what is called a component based architecture. This lets us as game developers combine behaviors in incredibly flexible ways.

To see why this is useful, it helps to understand that many games rely on object-oriented programming methods. You might have a monster class that defines general movement, hit points, etc. Then you create an archer sub-class that has all the properties of the monster, but also adds the abilities to shoot arrows.

This is a great technique, but you run into some problems. Say you have an archer sub-class and a warrior sub-class that can use a shield. It can be tricky to then create a new creature that can both fire a missile and use a shield. You could move both those abilities back up into the base monster class, but with dozens of abilities and billions of combinations, it can get messy very quickly.

In a component-based system, the behaviours like missile and shield are completely separate. That lets the designer (that’s me!) mix and match them together however I desire. Once I have a set of a couple dozen behaviours, the limits to what I can do are mostly my imagination. Do I want a timid wolf that runs from people but eats deer and turns into a giant ghost wolf if a pack of five are collected together? I can do that with just a few lines of code!

That lets me experiment faster, so that we can build a wide variety of interesting and unique objects (and it lets me hide all sorts of secrets in the game!)

Random generation

Here’s the other thing about Road Not Taken: like any good roguelike, its playfields are procedurally generated. You can’t memorise a solution to the game. You need to learn the behaviours of each animal or object in the environment and be clever about using those in each new context. Playing Road Not Taken is more like improv jazz than repetitive practice.

Failure is mastery

You’ll fail a lot initially. The first time the dark spirits emerge and suck your warmth away, you probably won’t recover. The first time you’re forced to abandon a child because you know you can’t reach them without passing out, you probably won’t feel so great.

But eventually, with a lot of cleverness, you’ll master the forest. You’ll rescue all the children. And then you need to deal with the rest of your life, which as it turns out isn’t so easy. What does “victory” mean when you’re still coming home to a sick loved one, or a stricken friend who can’t be helped?

But that’s a blog post for another day…

Join the Conversation

Add a CommentBut don't be a jerk!

11 Comments

Loading More Comments