God of War's director of photography breaks down three pivotal scenes that shaped the game's masterful cinematic style.

With God of War shipped and in the hands of our fans, I find myself contemplating the moments that helped define the new visual cinematic style we utilized for God of War. Each of these moments was a mental turning point, starting with “Can this be done with the tools we have?”, which moved onto “Can we pull this off without breaking our visual language?” and, mostly, ended with “I can’t believe we pulled this off.”

I’d like to share three of these moments, each of them defining a key cinematic milestone that paved the way moving forward.

Mother’s Knife

Cinematic challenge: Can we use traditional cinematic/visual storytelling when the disciplines required are cross-departmental while we don’t cut the camera?

Reading the first draft of the script, this scene drew my attention. Even though it went through quite a bit of iteration in production, the crux of it always struck me as pivotal. This is the last scene we experience before our heroes start the first leg of their epic journey. Establishing core empathy fundamentals and key tension points was critical. If not, why would we care about this journey in the first place? Our writers (Matt Sophos and Rich Gaubert) did a great job setting up these fundamentals and I wanted to make sure the message was delivered subtly, but in a clear and evocative manner.

- What’s the relationship between Kratos and his son? How do they feel about each other?

- How do they feel about the loss of the mother?

- How does Kratos feel about being a single father?

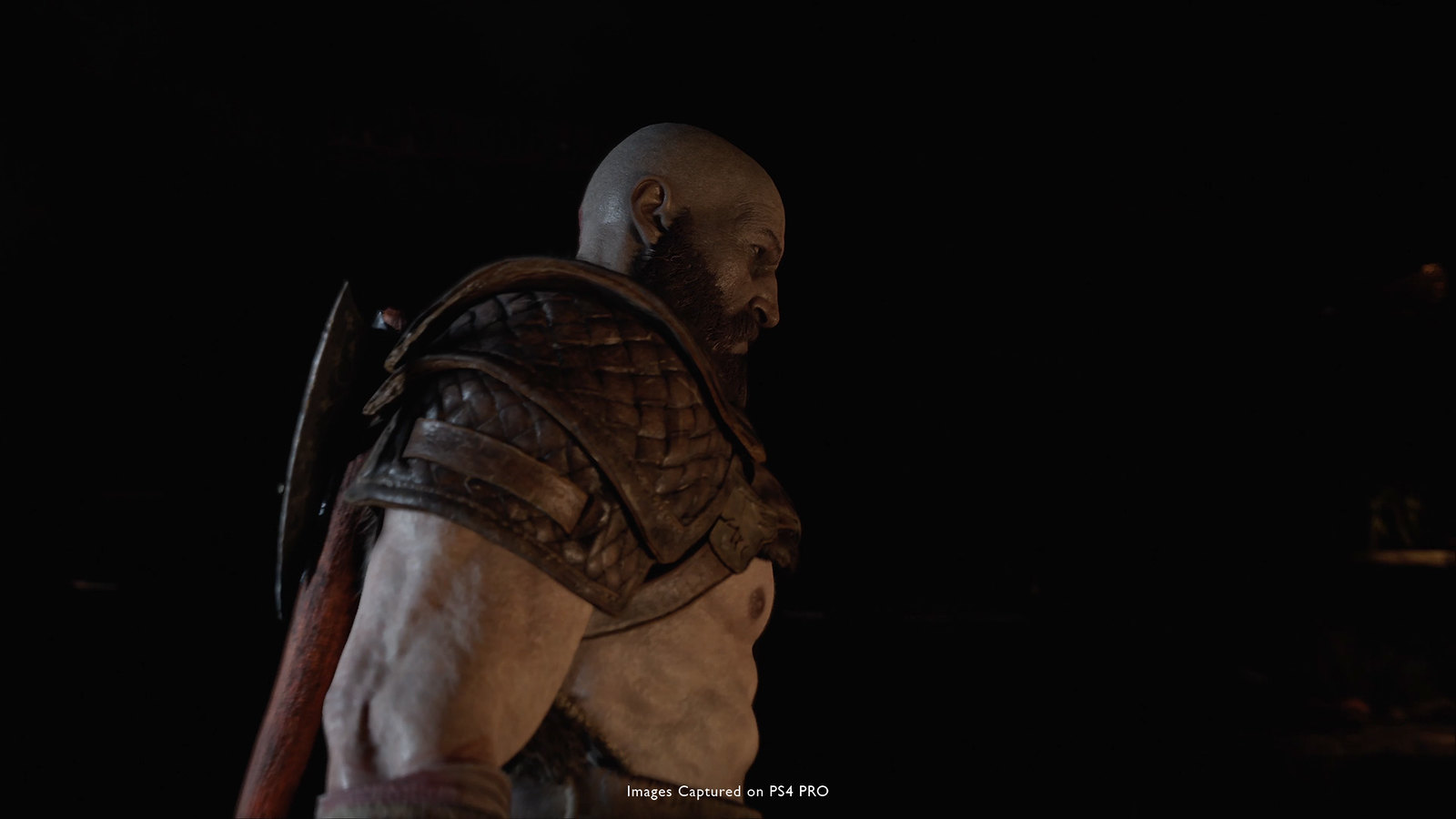

I decided to use the blue, cold, harsh tones of the “outside” to represent Kratos, Kratos as a father (at least at that point in the story) and the dangerous journey they have ahead of them. We used this light in sharp, high contrast for punctuation. We then chose the soft warmth of the indoors to define the rare safety the mother provided, using that to portray the softer emotions.

The challenge was staging the acting and camera to play against these two moods and to help define the core relationships and personalities, all without cutting the camera. Compounding these challenges were the technological limitations of creating sophisticated lighting models for real time rendered scenes. Our lighter (Greg Montgomery) did an amazing job balancing these assets.

Wide angle lens, emphasizing the environment, combined with the blue cold morning light. Atreus is outside, he’s in his father’s domain.

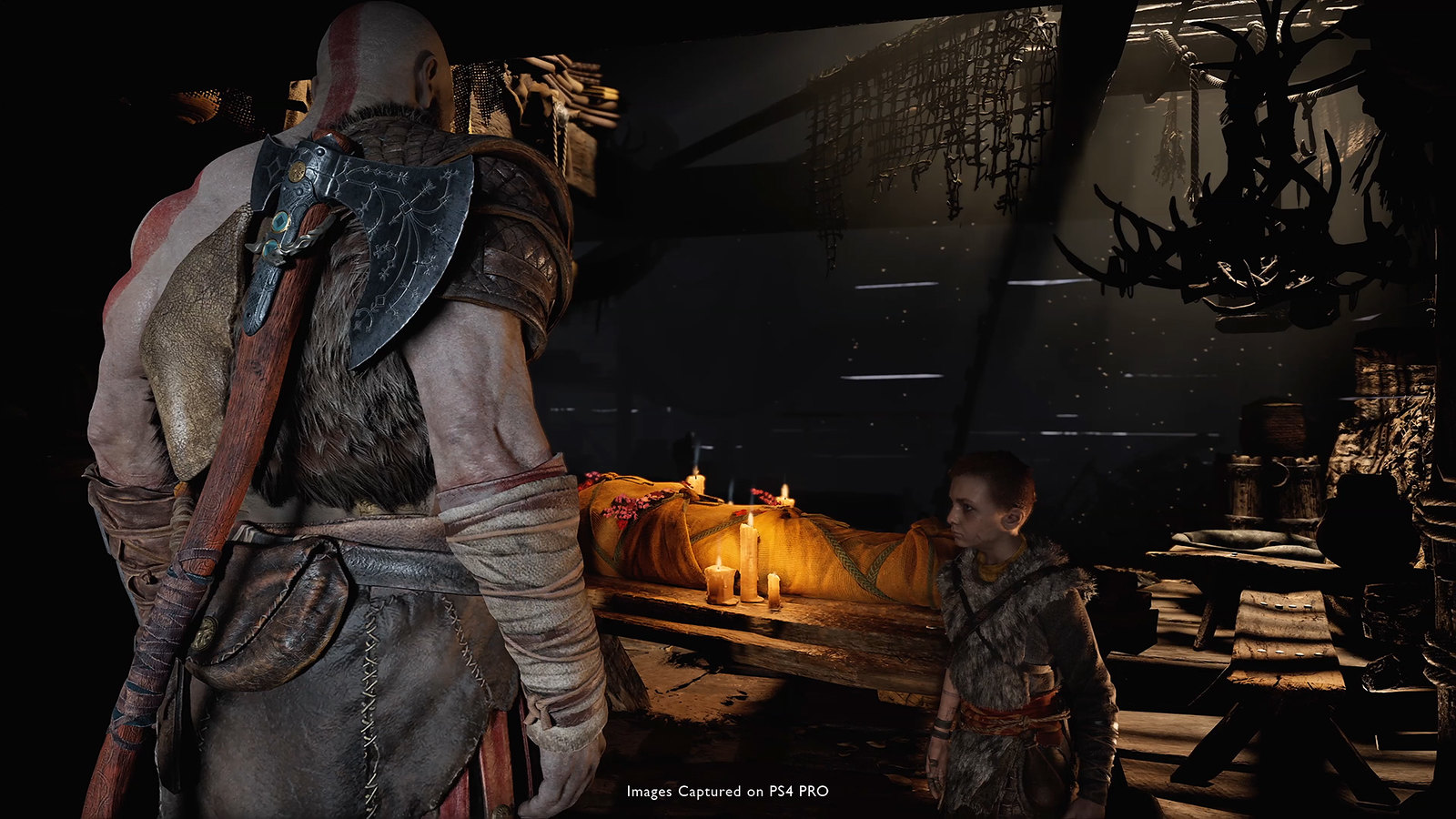

The door “wipes the shot,” revealing a body on the table. It’s lit in warm light, washing the interior with warm and safe mood. Atreus is still backlit cold.

The cold back light fades, Atreus is slowly enveloped by warm light. The lens slowly zooms, creating a sense of intimacy to partner with the lighting shift. Atreus is leaving the realm of his father and transitioning to the memories of his mother.

Soft warm light, tight lens, a sense of warm intimacy amidst tragedy. This is Atreus’ moment to mourn his mother. Kratos is no longer “in the picture.” Atreus is fully in his mother’s domain, where he has been all his life where he is comfortable… where he “belongs.”

Camera violently whips left, revealing Kratos, faceless, silhouetted in black against cold blue. The intimacy is broken. The image radiates “Pull it together boy, act like a man!”

Lens pulls back a little wider as Kratos takes over the scene. Just before he steps into the warm light of the candles, the camera orbits behind him, keeping him pooled in blue light. He just brought the “cold chill” into the room.

Atreus takes the hint; he musters up and collects himself, now washed in blue as well. He is no longer in the mother’s realm, he is now under the rule of his father. He wipes his eyes and steps off frame.

Atreus is no longer in the frame. Kratos is now alone. He no longer has to uphold the role of the stern father and he can now shift into the role of the mourning husband.

Camera orbits to give the sensation of “transition.” Kratos is wiped from cold blue to warm orange. He is still up lit, looking ominous. The emotion of the moment registers with him, but he is still the hard warrior, resisting giving in.

Kratos’ shell cracks, he leans into the light, the light is now soft, warm. He has entered the mother’s domain, revealing “softer” emotion for one of only three times he will do so in journey.

The brief moment is over. Kratos turns away from the warm light. We re-reveal Atreus, Kratos is back to being the stern father, his idea of what a relationship with a son is. They are both bathed in cold light. Back to the business at hand.

Two more beats resonated with me as I read the script for this scene. The lighting was strongly dictated by the environment at this point, so I chose to emphasize them in my framing and staging.

When Atreus drops the knife, we lose Kratos in the shot. The moment becomes all about Atreus and his need and deed. When Kratos is re-introduced into the scene, it’s with a gunslinger framing. A menacing shot, full of aggressive intent. Atreus looks at Kratos, his face reflecting that same doubt of “Uh-oh…” Then Kratos breaks the tension by leaning down, pulling a bandage off his own arm and bandaging Atreus.

We’ve seen how deeply Kratos cares about Faye, and how bottled up he is about his emotions. The funeral pyre is obviously deeply important to him. Here comes Atreus with his childish attachments, ruining everything. With this setup, my next instinct was “Kratos is going to hand him his a**!” But, Kratos surprises us and leans down to take care of Atreus’ burned hand. Whether he is trying to be fatherly, or merely making sure he can still function as a warrior, we don’t know. But that contrast struck me when reading the script and I wanted to emphasize it.

As Atreus comes back into frame, bow in hand, asking “what’s next?”, Kratos is out of focus. As Kratos responds, instead of shifting the focus back to him, we keep the focus on Atreus. Kratos speaks out of focus, lit by the warm light of the pyre, with a thousand-yard stare. He is not present. He is outwardly functional, giving Atreus commands, but his mind is elsewhere, mourning his dead wife. I felt it gave this moment that extra, subtle tension it needed.

Kratos is struggling with both the emotion of losing Faye and not knowing how to be a father to Atreus. He pushes Atreus into a world he better understands (“We’re going hunting”), though he is still in deep pain over Faye’s loss. The very end of the scene gave the perfect opportunity to emphasize this conflict.

Flying Boat Jump

Cinematic challenge: Changing point of view (from third to first and back) in order to push a sense of hallucination, while promoting empathy.

In this scene, Kratos is reliving a painful secret from his past: the moment he kills his father, Zeus. This display is part of Helheim’s mechanism to mentally torture its inhabitants. Kratos is hit by this vision two-fold; he is both internally struck by reliving it, and is shaken that his son is exposed to this part of his past, a part he has been struggling to hide from Atreus. On the other hand, Atreus himself is seeing his father, fully enraged and unrestrained for the first time — brutal, unbridled and violent. The challenge was how to do all the following without cutting the camera:

- Portray the brutality of the vision

- Portray Atreus’ reaction to seeing it

- Portray Kratos’ two-fold reaction to the event

- Bonus points: Portray it in a way that would evoke a sense of delirium, or being mentally off balance.

“Hell fog” rising from under the boat, leading Kratos’ attention away to a scene unfolding. Building up the tension, transitioning from current-day/older Kratos to a younger version of himself.

Kratos winds back a big punch; we use that body momentum to transition the camera to first person. We now are Kratos. Sharing in his moment of rage, reliving that moment from his past with him. This was also a good opportunity to pay homage to a very memorable moment from God of War III.

We use the momentum of the punches to swing the camera over and reveal Atreus; we’re back to the “real world.” Our empathy has shifted to experience this moment as a revelation to Atreus.

Something grabs Atreus’ attention. He runs back to Kratos, back to first person, back to us. We are again in Kratos’ head space, taking the moment in, taking in the fact his son has just seen one of the darkest moments of his past.

Atreus tells Kratos to snap out of it and point towards danger. We transition from first to third, experiencing Kratos’ struggle to break out of his reverie, adding to the sense of “delirium.”

It takes Atreus being in mortal danger for him to snap back into action.

Ogre Intro

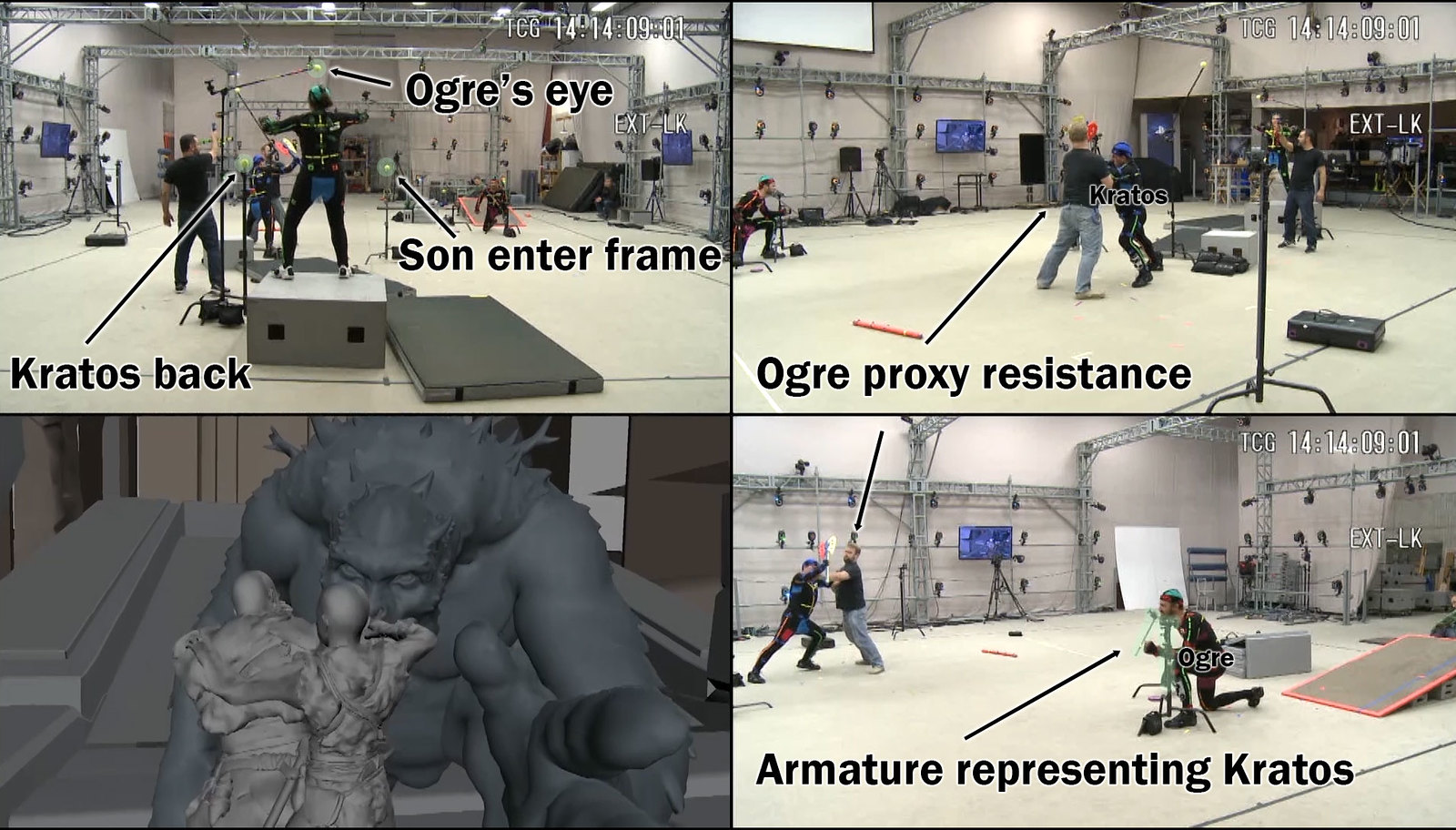

Cinematic challenge: Motion capturing a high action, high physical interaction scene with characters of different scale.

The previous two challenges were more about defining our emotional, cinematic language and how to execute it without cuts in a real-time engine. This challenge was more technical and helped define our approach to action. It helped us define which tools we’d need on set, and how far we could push real-time performance capture for characters with vastly different scales.

Large scale enemies are a core part of God of War’s visual language. Hence we wanted to address this key challenge early on.

Once I’m done staging the scene on paper, we move to rehearsing the action in “real space.” This step was critical in order to test whether or not the paper breakdowns were actually achievable and also gave us a chance to see all the “players” involved internalize the choreography and pacing of the scene. It’s interesting to see how “slow and safe” we took things at first.

Each actor played their role in their own “scaled space,” acting against props representing the other actors in the scene. This is why internalizing the choreography beforehand was critical.

Our roles:

- Bruno (our Animation Director) played Kratos

- Erica ( our Cinematic Animation Lead) played Atreus

- Mehdi ( our In-Game Animation Lead) played the Ogre

- Myself (Director of Photography) Staging, pacing callouts and “shooting”

All action was in sync, actors physically responding to each other, even though they had no real world contact. A well-oiled execution, the pre-planning and rehearsals paid off in spades. Ability to shoot multi-scale, single shot action scenes in real time… check!

As you can see in the clip, I shot this scene by looking at our on-stage monitors, using a stick to represent the camera. This test led to the realization that we needed to develop a far more sophisticated virtual camera system.

Going over these scenes, it’s incredible to see how far we’ve come. From exploring methods and ideas on how to execute Cory Barlog’s concept of a no-cut camera, to a clear, well-oiled, sophisticated and clearly defined visual language. At the risk of sounding cliché, it really does take a village.

Comments are closed.

5 Comments

Loading More Comments