Brain-bending puzzler Gorogoa is coming to PS4. Creator Jason Roberts considers the power a simple frame (or the lack of one) can convey.

On the occasion of Gorogoa’s upcoming release for PS4, I wanted to share some thoughts about the game. In particular, I’d like to talk about the power of the frame. It’s a subtle thing, but something I’ve thought a lot about while developing the game.

With the notable exception of VR, almost everything we consume is inside a frame, whether that frame is the edge of the TV screen, or the monitor, or the phone, or the movie screen. And we’re generally trained to forget about the frame and what’s outside of it. We want to forget ourselves, the room we’re in, the sorry old world we’re in. The disappearance of the frame is a big part of what we mean by “immersion.” We aim for total suspension of disbelief. Total projection of the mind through the frame.

And if you’re waiting for me to denounce this way of relating to media, I’m not going to! Why would I? It works just fine. But I also think that creatively, the space outside that frame is a huge unexplored frontier–as strange as that might sound at first.

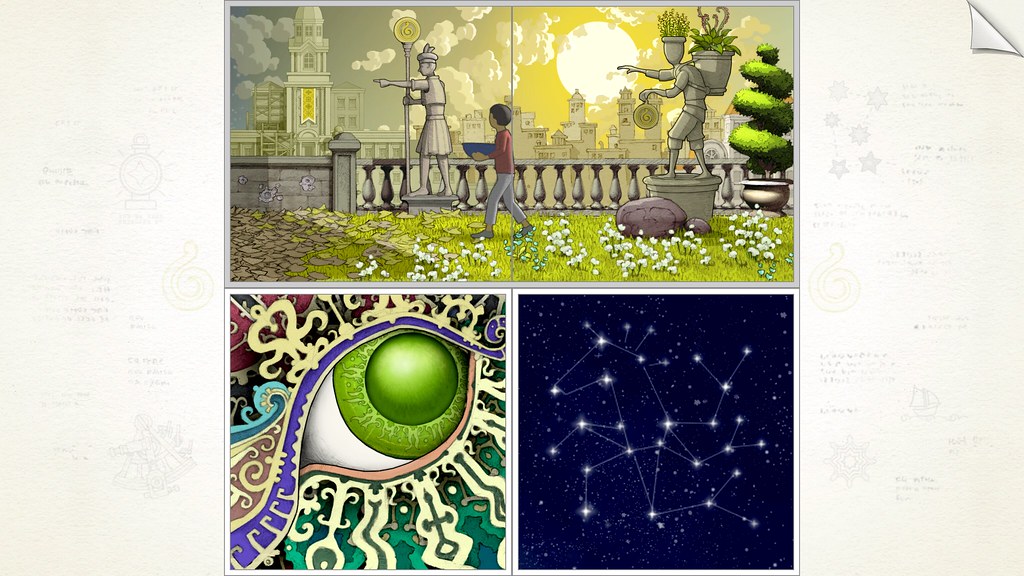

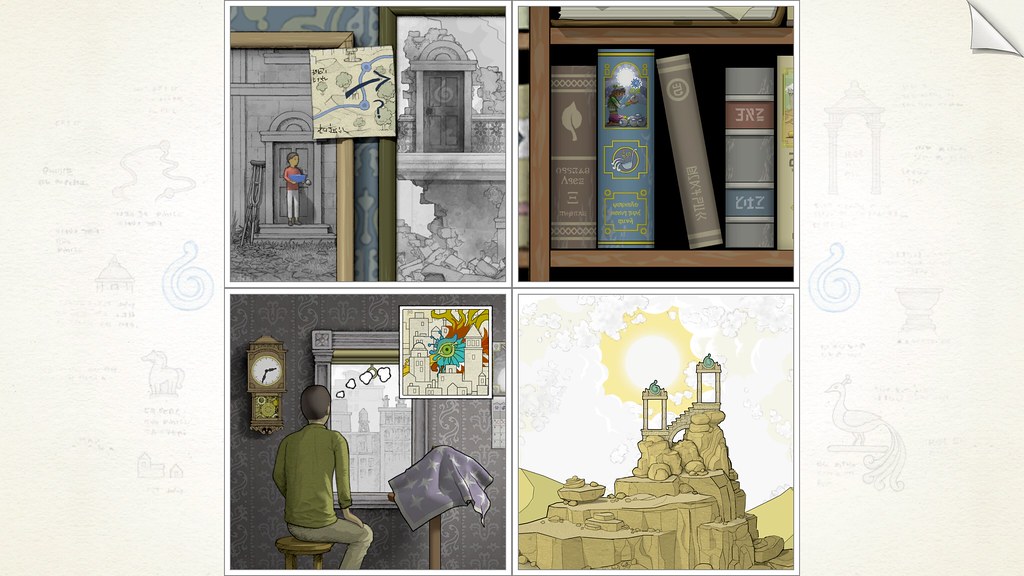

Gorogoa opens with a small framed image of a cityscape, in the middle of an otherwise empty screen. The obvious decision to leave empty space makes the frame visible, and that was done for a reason. The frame itself is part of the message. I find this mysteriously compelling. And I want to poke into that mystery a little.

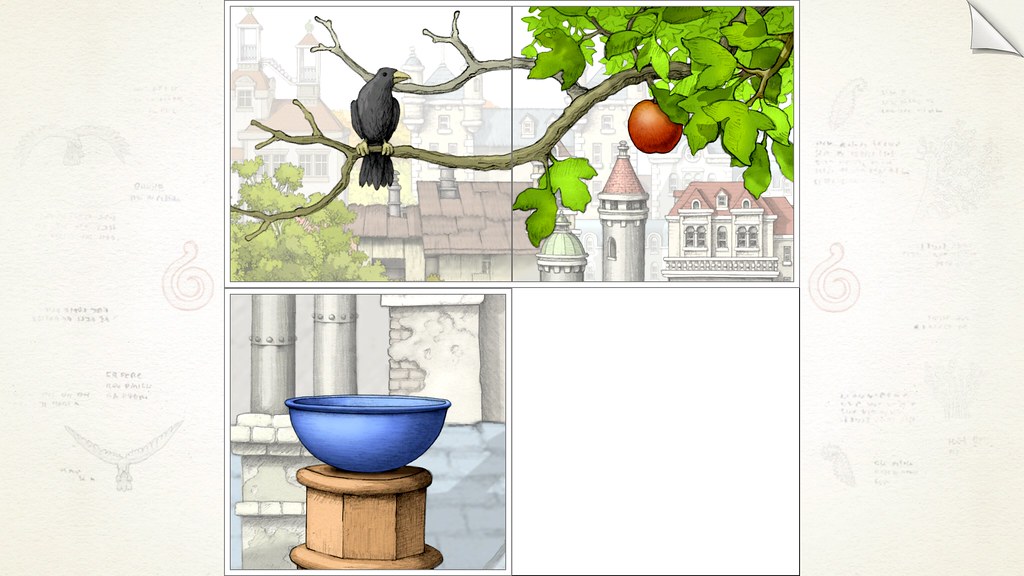

Consider the poignancy of sitting in a room looking out a window. Whatever you see out there, you’re separated from it. You can’t really reach it or be part of. Only your mind, your imagination, can travel out there. There’s a sweet, very human sadness to that. As I shrink down the frame and expand the space outside the frame, that separation between us and the scene, which we normally try to forget, becomes more apparent. The effect is a slightly more oblique, wistful relationship to the world inside the frame.

When I put a frame around something, it feels like a clue. A spoon is just a spoon, but a framed picture of a spoon is a message. If you’ve ever seen an empty frame hanging on the wall, you may have felt a flash of annoyance, because the power of the frame is being abused. It’s as if someone tapped you on the shoulder to get your attention, but when you turned around they were gone.

A frame is never neutral. It cares what it contains. Someone has chosen what to include and what to exclude. And they’re excluding almost everything. It’s an act of deliberate curation.

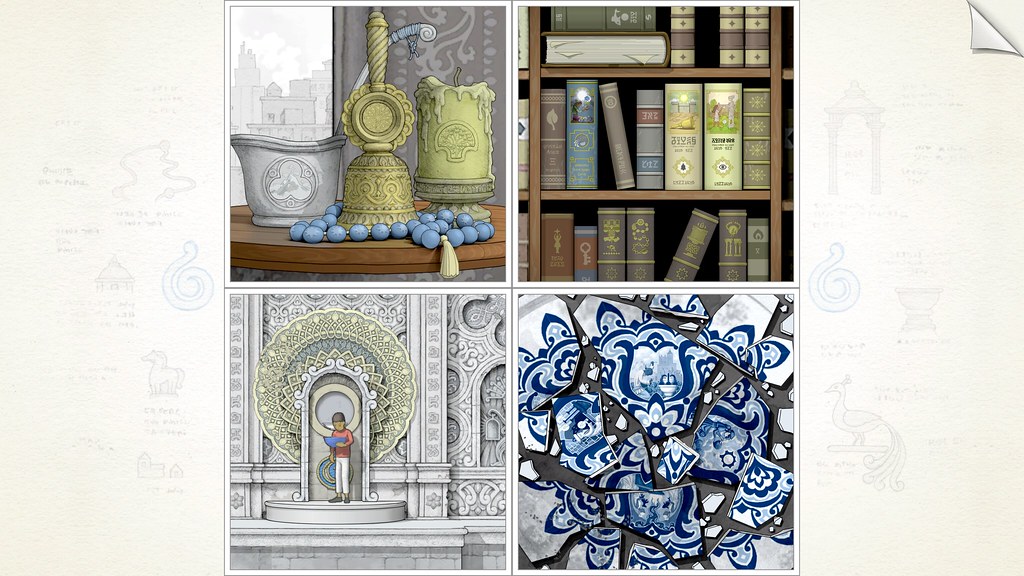

Often we see something inside a frame because it is precious. The frame is like a halo. We’ve built a special little box to cradle something valuable. Put a frame around something and it already has some of the feel of a religious icon.

Frames create mystery. How can we look at a frame without wondering what’s beyond the boundaries of what we can see? Maybe we unconsciously lean our head to the side, trying to peek around the edge. By making the empty space outside the frame visible, we emphasize that parts of the world are hidden from us.

And finally, a frame is a prison. Everything inside is boxed up, fenced in. And that creates a tension. Because if we see a prison, we want to see an escape. Even it’s only unconsciously, we want to see the frame broken. We want to see it transcended.

This frame hasn’t even done anything, and it already has all these amazing qualities. Or so it seems to me. And that’s before we even begin combining multiple panels. Once we start assembling framed images, we have a whole wall full of pictures; a whole gallery exhibition.

When we see a collage of images together, our mind fills up with heat lightning, working overtime to trying and find associations between the pictures. It’s like montage in cinema, except laid out on a plane instead of edited in sequence. Why have these images been placed together? Surely there must be some underlying logic, says the mind. Your inner conspiracy theorist starts connecting red strings back and forth.

And that’s before we add interactivity! Gorogoa begins by treating each frame like a separate game window. Within each frame we have the ability to zoom in on different parts of the scene. When we zoom in on an object, we place that object in the frame, as though we’ve chosen to hang a picture of it on our wall. We’re lending that object poignancy; making it into a clue; curating it; showing affection for it; and of course, imprisoning it. Just looking around becomes a much forceful act. This is what I find so compelling about this medium!

As for how these framed panels interact with each other, I don’t even want to spoil that much for people who haven’t played the game. See for yourself!

Comments are closed.

4 Comments

Loading More Comments