Hi, I’m Zoe Flower — Design Director at Hellbent Games and Narrative Designer for our indie horror game Wick. I have to admit that I never thought I’d write a sentence that included my name with the word “horror,” being that I’m the biggest scaredy-cat out there. Turns out though, making a horror game is a whole lot different than watching or playing one.

A year ago, I was merrily designing cotton candy colored worlds and stories for a LEGO game (About as far from horror as you can get!). But being an indie developer, you need to be quick to adapt. So when a publisher asked us how we felt about working on a big horror franchise, our Creative Director — and perhaps the biggest horror fan you could meet — jumped at the chance.

Some of us were a little more hesitant…

That’s not to say I hate horror games, having white knuckled my way through many a Silent Hill and Fatal Frame back in the day, even keeping my eyes open for much of PT (mostly out of respect for Hideo Kojima). But asking me to fully immerse myself in horror was a daunting task — part fear of facing what lurks in the dark and part fear that I lacked the skills to create something worthy of the genre.

But as it turns out, beneath the cheery LEGO surface, apparently I am full of twisted malevolence and darkness (Yay?!). While we didn’t end up working with that publisher, I was suddenly hooked on making a horror game. Which of course presented a larger problem for our little studio. Nearly the entire team was heads down in production, save a couple of coders and designers out of a staff of 20. But there is something beautiful in the challenge of building games within tight parameters, and we began to brainstorm just what was possible with a small team with an even smaller window of time to build something. We had a month to prototype something meaningful.

It wasn’t a tough sell to the team. Like any game studio, you throw out an impossible challenge and, after hearing “Can’t be done!” and “Designers are insane!” by the end of the week you usually have a multitude of possible solutions presented to you. Initially, we were compelled to make a rich story heavy adventure — Wick was almost an 80’s Babysitting Simulator (If you grew up in the 80’s, you can surely recall that particular horror!).

Eventually, we narrowed our focus to a much smaller concept. It needed to be one environment with a high tension mechanic that offered replayability. We studied the body of work that is the horror genre (Hello, insomnia!) — particularly Creepypasta and other indie successes like FNAF. We saw a pattern emerge, with a surprising amount of experiences operating on rails and often set indoors to maximize claustrophobia.

We loved the idea of being out in a forest (insert token Canadian joke here). But building horror without keeping the player on a single path presented a unique challenge. Can we make a game where you move how you like but the horror still finds you? And why are you scared in the first place? Lucky for us, humans tend to have common fears and we all agreed that being lost in the woods with creepy ghosts was definite nightmare fuel. But one environment, free-roaming, unpredictable horror with a high tension mechanic soon became the “impossible” challenge.

For a solid week we battled “can’t be done” until our programmer Neil landed on the concept of keeping dwindling candles alight to create safe spaces in a level. The mechanic held instant appeal and the first concept for Wick was born.

In its earliest form, Wick was a slow paced game of tense strategy, challenging you to locate fresh candles and place them around the level to create safe zones where enemies couldn’t reach you. But this iteration presented numerous design challenges — like how to define the radius of safety, what to do when players hid in corners or how to prevent a cheap kill from behind. It was also boring and not scary.

To solve this, we designed a creepy, organic, forest level to set the right mood for horror (designed by Chris Mair, our CEO with just a tiny bit of pedigree in level design including Counter-Strike’s DE_Train). The woods in Wick are an unsettling maze of continuous loops and turns, making it hard to get your bearings. The big bonus with a free-roaming space is that play becomes unpredictable — a keystone for creating a great horror experience.

As we began to explore our forest in first person, the candlelight mechanic changed dramatically. The only safety would be the light from the candle in your hand, making a much more intense solo experience that better supported the story that you are alone in the woods by the light of only a candle. We actually went out and did tests at night in the forest with just a candle. It is truly a harrowing and potentially deadly experience — mostly because you can’t see anything beyond your candle so you trip and run into blunt objects frequently. Wick uses a fair bit of poetic license.

The next step was populating the forest with diminishing candles so that the player is encouraged to keep moving. Again, this sounded good in theory, but in reality you really have no idea where you are or where the candles are (they are procedurally generated on every playthrough) so you tend to run in circles until you get killed by something in the shadows. The tiny twinkles in the fog were a brilliant addition to the game — hinting at where a candle is without giving away its exact location.

With a working candle mechanic, we had to face the much larger impossible problem of how to bring the scares to a player who is moving unpredictably through the level. We couldn’t guarantee they would cross any physical threshold to trigger an enemy or event. We couldn’t offer any narrative if we didn’t know where and when things would happen. Sure, we had a creepy level dotted with dwindling candlelight, but the gameplay was still only lurking in the shadows.

It was our programmer Stephen Spanner who dreamt up the solution and built what would become the heart of Wick. The guy has a deep passion for system design and Dark Souls — both of which heavily influenced the final design. Wick can be highly stressful and punishingly hard, thanks to a deviously intelligent system that takes a variety of measurements from your play style, then decides what to terrify you with next.

The event system in Wick guarantees you’ll likely never have the same playthrough twice. It also guarantees you will be terrorized no matter where you go. Candle light provides safety and keeps your fear metric at bay, but candles run out quickly. How much you run, how long you stay in the dark, and how quickly you cope with enemies all factor into just what the game will serve up. The power of the event system was a game changer for us. With a systematic approach, we found it much easier to design events and triggers that rewarded — and stressed/terrorized/punished/murdered the player based on how they approached the game.

Within a month we had a solid core loop for the game! But there is no rest for the wicked — we still had no idea just who or what was hiding in our forest.

Designing a believable urban legend is a unique process. I grew up in the woods of the Great White North and not a camping or canoe trip went by without rumors of a ghost/serial killer/lake creature/haunted cabin/missing kid, so I had plenty of material to draw upon. But of course, we had no time or resources to produce complex animation, or professional acting. And even the best cinematics can’t do justice to the horrors in your own mind. So we used that to our advantage.

I really love the opening scene to Wick. It may not seem like much — a black screen with white type written to suggest a police officer’s file, teenagers talking over each other on their way to play some game called “Wick,” then straight into gameplay with no tutorial or explanation. While the scene feels simple, it is highly effective at suggesting a story without needing to tell one.

Once in the forest, you start to see and hear the breadcrumbs of a darker tale. There are layers of story to explore if you aren’t too busy just trying to stay alive (Thanks, Dark Souls!). Using a “found footage” style with plenty of notes and strange objects — all accompanied by suitably creepy audio and dialog — we brought our urban legend to life.

As for all the voices you hear throughout the game, we bribed, borrowed, and begged our staff (And their families… and friends… and even some local high school drama students…) to read for us. Chris — the same guy who is CEO and designer — is multiple voices in the game. The format was so effective that he had his son Maceo take up the torch in our “No Way Out” bonus chapter- recording over 800 lines of audio for “TBubber!”

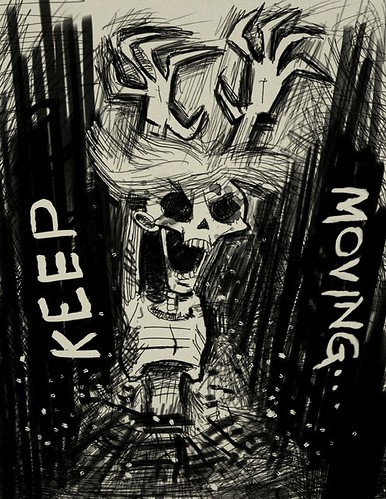

Of course, we couldn’t make a game that relied on the player’s imagination alone. Designing enemies was by far the biggest challenge in Wick. The story was getting darker and darker by the day, as I spun tales of deranged children and evil twins (strange because I actually have two kids and they are lovely). While writing the characters was easy, creating the look and the functionality for each child became a design and balance nightmare. Our core event system was potentially limitless but each event — whether audio, animation, encounter, or attack — had to be carefully thought out to ensure it worked in every scenario the player could put themselves in.

“Can’t be done!” made a comeback in the office that week.

Wick plays out by the hour as you attempt to survive from midnight to 6:00 AM. Initially, we tried just one enemy per hour. Then we tried increasing the number of enemies each hour culminating in a crazy hard “survive them all” level. But the ramp made the game feel too repetitive. Eventually we came up with the idea of mix and matching different kids together whose mechanics balanced each other in unique ways. You start out playing with Tim and later meet him again but now he’s in the forest along with Tom, or perhaps Lillian, creating a new strategy to how you play through that hour. We even built custom events where the enemies work together with joint encounters and attacks.

After just 5 months, we found a balance and finished the game. The forest is rich in atmosphere (We love fog!) and the audio creates the perfect sense of mystery and dread. The enemies stalk and hunt you ruthlessly and there are clear paths to success if you can figure out a strategy. The game is punishingly hard and highly replayable.

Wick isn’t a large game. Nor is it a perfect game. But it is a free-roaming unpredictable horror game where the scares come to you. Try and survive the night starting November 1 on PS4. A word of advice though… stay in the light. And as a tribute to overcoming the impossible, we dare you to unlock the bonus content in our No Way Out chapter.

“Can’t be done!” you say?

Comments are closed.

9 Comments

Loading More Comments