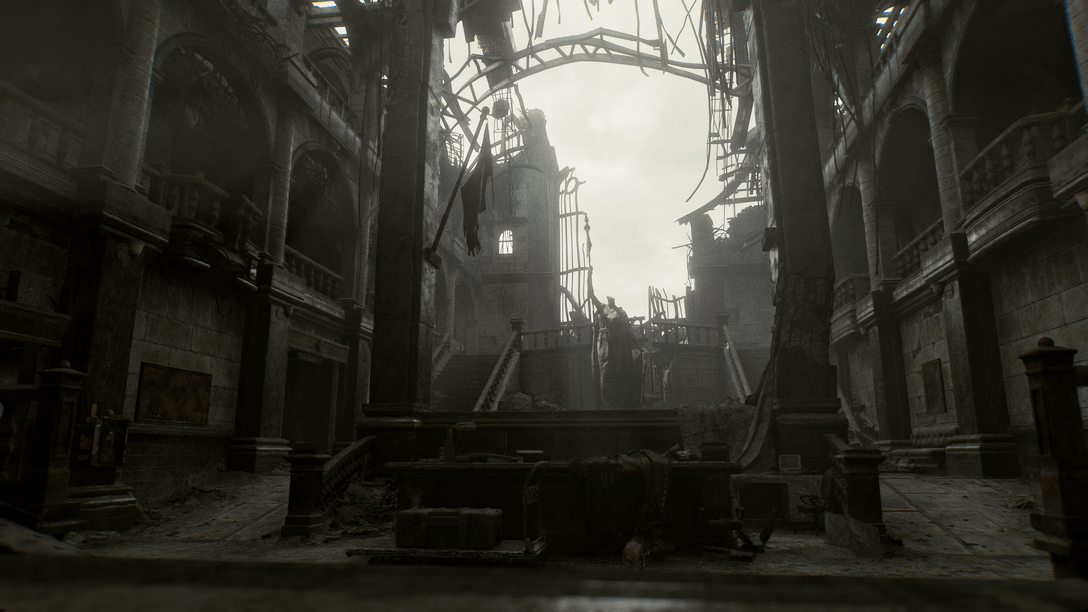

As with any jump from one console generation to the next, PlayStation 4 owners will expect to see hardware that sits at the very cutting edge of innovation, offering unparalleled processing power and an arsenal of exciting new features.

However, the onus on game developers to bring bold new gameplay innovation to the table is every bit as integral to that generational leap, and it’s a responsibility that the whipsmart team behind Ubisoft’s future-tech open world action title Watch_Dogs are really tearing into.

As detailed in our coverage last week, the game’s core conceit – that its central hero, hacker Aiden Pearce’s primary weapon is not a gun, but an entire city – is one of the boldest, most ambitious ideas to come along in some time. To find out more about the game’s attempts to re-write the action rulebook, PlayStation.Blog sat down with the game’s creative director Jonathan Morin.

Jonathan Morin: It started as a conversation. Four years ago we were talking about humans exchanging their lives and their details through their phones, and about how that could change our everyday lives.

When you make a new game where the mandate is broad and you have the right to create something new, you want to make sure that the people around you are all working on a subject they’re passionate about – something they really want to explore. So listening to those conversations helped come up with ideas. Like, “we all want to dig into these issues, so let’s try it out.” As the conversation grew, we started to add crazy ideas, like the profiler, and when you start prototyping those things, that’s when it explodes.

PSB: You started development four years ago. To many people, that might seem like a very long time to devote to one game…

JM: Well, there’s always a conception phase where there’s not a lot of people involved. We were only 10 for a long time, then we were 20 or 30. You need a certain kind of people – people who like to dig into subjects and research, try elements out and be comfortable with failure. Those were the kind of people we had.

It was a long process to define what was going to be special about the game. It was pretty early on when we ended up talking about controlling an entire city. The traffic light hack was one of the first prototypes we did. That really generated an emotion. “Woah, what? Can I do it on the other one too?”

That’s the kind of thing where you say to yourself “the promise of doing this is insane.” But you need to make it real and build a system around it that works. So those four years became a big challenge for some very smart people.

JM: Not really. There’s no real compromise there. It’s a very broad subject and had a tendency to create an infinite number of ideas when you brainstorm it. There’s a moment when you have to say “let’s stop here, let’s not go there”.

I don’t see that as a compromise, I see that as a necessity. If you want to make a game that has quality and in which everything reacts with each other in an elegant way, the only way to pull it off is to understand the barriers.

Constraint can be seen as a negative from the outside, but when you’re on the inside, having clear constraints helps people produce ideas faster. The constraints are re-assuring. This is where we stop. Then the rest is like, if there’s a subject that is bigger than just one game and there are a lot of ideas, and it’s successful, well… that’s not a problem, it’s a good thing.

PSB: And what about Aidan Pierce? How did his character take shape?

JM: One of the big things about Aidan Pierce is that he’s very street smart. We had a lot of conversations about that. It sounds straightforward, but very early on we looked at a game like Assassin’s Creed and how characters are and how they move. One of the things we felt was missing in every game was contextualisation. All those guys feel like robots. They move in the same way regardless of the situation.

Can we change that? Someone who is smart and is supposed not to attract attention to himself is going to walk in a certain way, and is going to be aware of his surroundings. So we put a lot of effort into that contextualisation. And that influenced everything, especially his look.

Like his mask. If there’s press and media in the game universe, he needs to react to it. Contextually he’s going to put his mask on when he starts doing bad things so that he’s not noticed.

The hat? He doesn’t want to be seen, so he can pull the brim down – like all those actors in Hollywood trying to avoid the paparazzi. They always have caps on. It’s cool, it’s different. The hoodie has been done to death.

The coat – same thing. It hides a lot of his body and he can hide things underneath. It’s also a cool way to interact with the wind physics and create nice continuity of movement. It creates a second wave of movement. It feels a lot more realistic for the player.

It sounds very easy and smart but it took years to have these ideas. Iteration upon iteration.

JM: The experience is the same. We’re not removing anything from the core experience on either platform. We’re not eager to create a game for a machine. We’re making a game because we think it’s cool. When you create an idea you shouldn’t base that idea only on what’s possible or impossible to do on a machine. If you do I don’t think you’re doing the right thing.

When PS4 showed up, there was definitely a portion of the game we could push forward – the wind simulation, the water, the realisation of certain AI behaviours. So those elements are magnified versions of the core experience in the next gen.

PSB: What aspect of PS4 has surprised or excited you most?

JM: One thing I like about the PS4 is its philosophy, which from a creative perspective is an important thing. I think the next generation of games will be more than ever at the service of the player. Players are now the ones who drive what next gen should be. They’re connected all the time. The way they live their lives are different. So we need to pay attention to how society changes to give them a form of entertainment that is a natural extrapolation of that. I think that Sony understands that.

PSB: I know you’re leaving your big multiplayer reveal for another day, but can you talk in general terms about how you’re approaching that part of the experience?

JM: You can play single player or multiplayer in the game. You’re always in your own session. If you’re playing alone, you’re playing alone. So it means there are millions of people alone in their own sessions. We’ve simply added the ability to merge those sessions together at the pacing of our choice.

You can be free-roaming and naturally getting into some kind of activity that makes you intertwine with another player. You interact with them, then you’re done and it goes away. It’s not like you have someone in your game the whole time who can mess with your game, but it’s definitely the beginning of a solution to tackle those taboos.

Players often worry that another player is going to come into their game and break their experience. That’s an old school statement. We need to fix that, and it’s a design problem, not a technical problem – how do you bring two players together and let them interact in a way that’s pleasing?

One thing I can say is that when we watch people play together in Watch_Dogs, most of the time they don’t even realise that it was another player. There are no signs. There is a great thing there that someone can be in the experience and naturally enter a situation. They become part of the story. “That was another player? No way! That’s awesome!” They didn’t notice. That’s spectacular!

As a developer, I can immediately tell when it’s another player in a game – jeez, that guy doesn’t walk like an AI, that’s a player. But in Watch_Dogs, players won’t notice that immediately. It’s a new form of emotion and it fits perfectly in the Watch_Dogs universe where everybody watches everyone else.

Comments are closed.

21 Comments

Loading More Comments